Ideological Catholicism and the Great Commandment

Posted by Anonymous in Church Doctrine, Theology on 1.26.2010

The contemporary scandal of "Liberal" and "Conservative" Catholicism is nothing other than Satan's victory over our strengths, that is right, our strengths. The Evil One likes nothing more than to turn a great good into a vice, through the exploitation of good intentions. The situation is actually a distortion of the great two tiered commandment which the Lord Himself taught us.

On the so called "Liberal" or "Progressive" side of the "Catholic spectrum," everything tends to implode into the second part of the great commandment so that social justice, soup kitchens and committees which "build community" become the center of our Christian experience. The faith thus becomes flattened and the vertical dimension vanishes, only to be replaced by an all inclusive "faith based" social network to promote human flourishing which in turn becomes a substitute for faith in the God Who reveals Himself in Jesus Christ. People forget that philanthropy and human compassion do not equal Christian charity. Many people who are pro-abortion and pro "gay marriage" are very generous in their donations to humanitarian programs. One need look only to Hollywood and even in our own cities. Giving money to poor people and working in a soup kitchen, as noble as these actions are, do not equal a morally virtuous life or a right relationship with God.

On the so called "Conservative" side of the "Catholic spectrum," everything tends to be imploded into the first part of the great commandment so that Church initiatives and speaking out against abortion and homosexuality become the center of our Christian experience. Defending the unborn and standing up for the traditional family are not only laudable, but they are necessary for every Christian. However, they are not enough, such that they exhaust the conditions for entering into life [salvation]. "Conservative" Christians also must be generous with the poor and live a life that is sober and temperate in its habits of consumption and lifestyle. They need to make their proper contribution to whichever community they find themselves in and not trick themselves into thinking that talking about holy things makes one holy. Orthodoxy, right belief, does not equal orthopraxy, right action. Only both, together at the same time, fulfill the condition for "entering into life."

The Evil One's trick is to make people focus on one part of the great commandment to such an extent that they neglect the other. This twisting of goods imperils one's soul precisely because one cannot love God, whom they have not seen, if they do not love their neighbor who they can see. They, however, cannot love their neighbor well who do not love God through right faith, conversion and prayer. The awful condemnation that God utters towards those to be cast into "eternal fire" is because of neglect toward their neighbor in charity.

In the Office of Readings for the second Sunday after Christmas, Saint Augustine writes the following:

Let us beg the Lord to avoid the traps of ideological Catholicism and pray that we become faithful, loving Christians in a world where the light of faith risks being extinguished.

Faith, Reason & Existentialism?: A Reconciliation

Posted by Andrew Haines in Philosophy on 1.16.2010

Three words that don't normally go together—that's for sure. But what do our understandings of faith, reason and existentialism have in common?

Frankly, I think, quite a bit.

Considering the relationship between faith and reason—as the followers here at IUSP know—is simply a part of the Christian life. Creation is both reasonable as well as mysterious, and in order to apprehend it completely, we must be willing to implement our rational faculties on both levels (viz. the levels of empirical observation as well as the penetration of what lies beyond). Faith and reason, for the Christian, are inextricably related.

But how do they relate to "existence"? Or, for that matter, to the ever-popular but rarely-understood phenomenon of "existentialism"?

If you're guessing the title of this article was a ploy by the author to pull in some extra Google hits, you wouldn't be far off. But I never disappoint! There is a connection, I assure you; but before diving right in, we have to frame the question a little more completely: What is existentialism, after all? And why should we be concerned with it?

What is Existentialism?

Most basically, existentialism is a term that denotes some sort of primacy regarding the act of existence itself (the actus essendi, for you Thomists). By and large, no matter their creed, upbringing or historical circumstances, existentialists always tend to focus on this precedence of "being" over and above that of "essence" (or formality). Still, however, the word, "existentialism," is about as generic as "philosophy"; and there is really no textbook definition worth memorizing. Different brands of existentialism (materialist, atheist, Christian, etc.) all understand their own purpose differently, and it's hard to put a finger on any sort of universal, 'existentialistic essence.'

But, despite its somewhat opaque definition, the idea of existentialism is one not far from the heart of the Christian intellectual tradition. In my estimation, a sort of existential hermeneutic is very helpful in unlocking the deep connections between faith and reason, and between the existence of God and the existence of things in the world.

But, despite its somewhat opaque definition, the idea of existentialism is one not far from the heart of the Christian intellectual tradition. In my estimation, a sort of existential hermeneutic is very helpful in unlocking the deep connections between faith and reason, and between the existence of God and the existence of things in the world.

Existentialism in St Thomas Aquinas

As it turns out, a certain application of existentialism can be found even in the work of St Thomas Aquinas—the Christian philosopher most often pitted against modern trends—who accounts for the relationship between God and the world on the basis of the preeminence of "being," or esse. (Thomists of the Strict Observance, prepare to strike.) In the words of the famous 20th century Thomist, W. Norris Clarke:

"[...] actual existence [for Thomas] is not merely a static state or minimum 'fact'—i.e., the mere extrinsic referent of a true assertion—but an intensive inner act of presence within the thing itself which grounds the mental assertion about it: a kind of qualitative energy (virtus essindi [sic]: the power of be-ing, in St. Thomas’s words)." (The Philosophical Approach to God, p. 62)

In layman's terms, Clarke's position (and my own) can be translated thus: that for something "to be"—to exist—is not simply for it "to-occur-in-accordance-with-its-formal-definition"; but rather, each existent thing possesses of itself a certain "power of be-ing" that propels it, as it were, along its life in the world.

At bottom, Clarke's understanding of Thomistic metaphysics can very rightly be termed "existential." But it is an existentialism grounded firmly and without apology in an assent to the existence of God on the basis of rational, intelligible evidence in his primary (and necessary) act of existence. And, moreover, it is a theory that resonates strongly with the way we, as individuals, experience the world around us: namely, not as some "static state" of "minimum facts," but as invigorated and vibrant.

For those familiar with Thomas' emphasis on "participation" between finite, created objects and their divine and exemplary forms in the mind of God, this Christian existentialism has even more force. For Thomas, we are able to regard "being" as primary precisely because God's "being" (his esse) is synonymous with his essence; and this purely actual essence, which contains in itself the exemplary forms of all created objects, propels those objects into the world, and creates them in the same act by which it knows them. Si secundum unam causam Deus omnibus existentibus esse tradidit, secundum eamdem causam sciet omnia. (De Ver. Q. 2, A. 4)

Existentialism, Faith and Reason

Here, we can make a few connections between faith, reasons and existentialism that were before less apparent. In fact, we can even begin to understand existentialism—in a certain application—as that which links the other two.

If, as St Thomas suggests, a thing's (rational) intelligibility is bound up entirely in its conformity to some exemplary idea—and if its actual presence in the real world (ens reale) is charged with a "power of be-ing" that can only come from something beyond its basic materiality—then we have real reason to believe that a more supreme, absolute Being is ultimately its cause (even if we can't see or touch this Source directly); and we call this Being, this Source, "God."

Ultimately, to redeem "existentialism" from its unfortunate bonds of 20th century, secular humanism and atheism is a big charge; but it's not insurmountable. Existentialism is not inherently opposed to Christian faith, and to the value of informed reason. And, on the contrary, in some ways it is the truest expression of that faith. When discerned through the lens of the existential hermeneutic, reality becomes even more alive, and even more "Christian," in the fullest sense of the word: God, its Source, is made ever more tangible by way of the universal "power" of existence; but he is still divine, and although he 'touches' the world, he is not a part of it.

References

Clarke, W. Norris. The Philosophical Approach to God: A New Thomistic Perspective.

(New York, New York: Fordham University Press, 2007)

Benedict, Marini & the Importance of the 'Reform of the Reform'

Posted by Andrew Haines in Church Doctrine, Liturgy, News, The Holy Father on 1.11.2010

There's been a lot of buzz lately in the Catholic news outlets about one of my favorite topics: liturgy. And I'm eager to share a few thoughts of my own on the matter...

There was a time in my life (not all that long ago) when "liturgy," for me, was not much more than a physical expression of some poorly-formed and weakly grasped ideology--one that took issue with Reformation-esque practices as (in the words of Hilaire Belloc) a "profound cleavage" from the traditions of Roman Catholicism. But, at the heart of my rash reactionism was a poor understanding of just what that Roman Catholic tradition meant for the history of Western civilization as a whole; and, accordingly, a grasp of what the Protestant influence meant for its future.

I've come to the (slightly) more informed realization, recently, that the Church's influence on culture and tradition has not merely offered a sense of universal significance to something that was otherwise without, but rather that its very importance is entirely and inextricably united with the basic, cosmological significance of history and tradition as it has always unfolded and developed. And nowhere is this more clear than in the Catholic liturgy.

Thankfully, this opinion is more than simply personal. And, in the last few days, it has been echoed strongly by papal emcee and liturgist, Msgr Guido Marini, in his comments regarding the "reform of the reform" of Catholic liturgy. In short, Marini asserts that the liturgy celebrated by the Catholic Church should have a character of historical continuity. "I purposely use the word continuity," says Marini, "a word very dear to our present Holy Father. [...] He has made it the only authoritative criterion whereby one can correctly interpret the life of the Church." (CNS)

Thankfully, this opinion is more than simply personal. And, in the last few days, it has been echoed strongly by papal emcee and liturgist, Msgr Guido Marini, in his comments regarding the "reform of the reform" of Catholic liturgy. In short, Marini asserts that the liturgy celebrated by the Catholic Church should have a character of historical continuity. "I purposely use the word continuity," says Marini, "a word very dear to our present Holy Father. [...] He has made it the only authoritative criterion whereby one can correctly interpret the life of the Church." (CNS)

What is more "Catholic" than "catholicism": that is, universality, interwovenness, and the highest sense of "continuity"? And, conversely, what is more "Protestant" than an affront to such continuity (often expressed even overtly in terms of "non-denominationalism" or post-enlightened "egalitarianism")? If there is no clear series of precedence, then there is no possibility for continuity.

What I saw initially as a "profound cleavage" from Roman tradition--the Reformed infiltration of the Catholic liturgy--was a valid perception. But without attempting to comprehend the absolute depth of such cleavage, my mindset was one aimed merely at fixing the problem at hand, and not at seeking to repair the damaged roots of a thorough and complete break with the sensus fidei. "The liturgy cannot and must not be an opportunity for conflict," says Marini; yet the reformist mentality of the late 20th century amounted almost entirely to nothing but a conflict with the stated and perennial traditions of the Church for centuries before.

As Marini is keen to point out, the real work of faithful Catholics in the 21st century--for those who wish not simply to profess the faith, but to live, preserve and pray it by their deeds and practices--lies in promoting an understanding of the liturgy that is, above all, wholly Christian, and wholly undivided and non-partisan. "Fixing the glitch" is not a sufficient response to the deep wounds inflicted by the Protestant mentality of spiritual individualism (or what Belloc calls the "alienation of the soul"). Instead, Catholics must follow the example of the Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, by further grasping the true meaning of liturgy (theologically) and by evangelizing their fellow Christians on its deep importance in the life of faith.

"I have learned to deepen my knowledge these past two years in service to our Holy Father," admits Marini. "He is an authentic master of the spirit of the liturgy, whether by his teaching or by the example he gives in the celebration of the sacred rites."

Indeed, Pope Benedict has never modeled an attitude of reactionism; but instead always an attitude of genuine appreciation and profound love for the beauty of the liturgy that is possessed simply by virtue of its supernatural character. Benedict and Marini speak of the "reform of the reform" not because they are Reformers, but instead because they realize the importance of eradicating the very mentality of the Reformation by way of a thoroughly Catholic "hermeneutic of continuity."

The 'Prosperity Gospel' in Action

The "prosperity gospel" is a phenomenon well-known to Americans: it makes prayer equivalent to monetary donation, and salvation coincidental with prosperous financial success. And it's a lie.

More than simply distorting the words of the authentic Gospels of the Church, the "prosperity gospel" distorts what is at the heart of Christian teaching—namely, to surrender oneself to the divine Providence, and to approach God not with grasping firsts, but with open palms. In short, it transforms true Christian divinization into that of a pagan cult.

In the video below, an American camera crew explores the ravishing effect the "prosperity gospel" is having on African nations. In the face of abject poverty, they are willing to do anything to survive; and pitched to them in the words of the 'gospel,' prosperity looks ever sweeter.

The Prosperity Gospel from The Global Conversation on Vimeo.

For an interesting take on "prosperity" evangelization, check out this post from Jordan J. Ballor at the Acton Institute's PowerBlog.

Wisdom Vindicated by Her Works

Posted by Andrew Haines in Biblical Commentary, Prayer, Theology on 12.11.2009

The Lord speaks clearly today in the Gospel for those who put an emphasis on learning and knowledge: if one is truly knowing and wise, then he will be vindicated by his works. (cf. Mt 11:19)

It's always a struggle to discern whether or not, as a teacher, I'm educating my students in the best way possible. I am continually forced to ask myself the question (and "forced" is no understatement): am I acting in the name of divine Wisdom, or in the name of selfish expectation?

This morning at Mass, I was comforted (and challenged) by the words of Scripture: "Wisdom is vindicated by her works." Of course, this leads me to think that the only reasonable alternative is that selfish expectation is condemned by its works.

Nonetheless, contrary to our own intuitive designs, the greater glorification of God often comes by insuring that those in our charge (as Christian teachers of the faith) will be made capable of glorifying God freely in their own lives.

As I reflect on Christ's words to his disciples--that "wisdom is vindicated by her works"--yesterday's Gospel passage comes to mind, in which Jesus speaks of John the Baptist as the greatest of all men born of women. (cf. Mt 11:11) It was John's entire kerygmatic leitmotif that he must decrease while the Messiah must increase. (cf. Jn 3:30)

And it is the same passion that must infect every Christian teacher: namely, that the glory of God must increase in the aggregate, while selfish expectation decreases in the individual. Moreover, we must believe that if we teach the Wisdom of God authentically, and with dedication to the intricacies and beauties of its form, God's glorification by the many will be the glorification of God by the teacher. After all, since Christ is the true teacher, what else can we do than make ourselves as small as possible, and know that God himself--in his Wisdom--will vindicate our works of humility and virtue?

This is a monumental charge for anyone, and particularly for me, still seeking the grace fully to allow the Lord to be glorified, instead of expecting to glorify him by my own merit.

Please pray for me, and for my students.

To Russia with Nuncios

Posted by Andrew Haines in News, The Holy Father on 12.10.2009

Who calls Russia by its official name: the Russian Federation?

Apparently the Vatican press office, which recently released a statement indicating that Rome and Russia are soon to be trading top agents.

According to the Vatican Information Service, "the Holy See and the Russian Federation, in the desire to promote their mutual friendly relations, have decided by joint agreement to establish diplomatic relations, at the level of apostolic nunciature on the part of the Holy See and of embassy on the part of the Russian Federation."

Pretty straightforward news—but equally as groundbreaking.

The new concord comes after Thursday's meeting of Pope Benedict XVI with Russia's premier, Dmitri Medvedev. But despite the "cordial" atmosphere of the encounter, Vatican officials are saying that a papal visit to the Kremlin isn't likely. (New York Times)

Still, if the Holy Father's recent dealings with the Eastern Orthodox patriarchs have anything to do with this...I wouldn't rule such a visit entirely out of the question.

A Worthy Project

I've got a bit of a guilt complex about using In Umbris Sancti Petri as a launchpad for other projects but...

...for those who haven't, please consider checking out the work being done over at ProLife ProPatria. If you like what you read here, you will most certainly enjoy the discussions there!

Since founding ProLife ProPatria about one year ago, Matthew Barry and I—along with a whole new team of writers, editors and consultants—have been plugging away, making our website as worthwhile and informative as possible. And now, finally, after a year of hard work, we think we're onto something big.

In the beginning of 2010, we'll be making a push to incorporate ProLife ProPatria as a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization. This will help us to solidify our structure, bring on-board even more top-notch authors and editors, and provide the basis for financial stability over the next years.

Currently, we are looking for anyone who might be able to offer valuable connections (individuals, companies, dioceses, universities, etc.) that might help us to get off the ground in a real way, and maybe even form long-lasting partnerships in this important field of bioethics and Catholic social theory.

Over the last month, In Umbris Sancti Petri has seen "hits" from viewers around the globe—from 62 countries, and 36 states. I hope that you all who've been reading these pages will consider supporting an even greater project; and that you'll pass the word on to friends and colleagues who may also be interested.

For now, I'll do my best to keep things up-to-date here (as well as there).

Oh, and did I mention that I'm getting married in a month?!

Benedict: The 'True Philosopher'

Posted by Andrew Haines in Philosophy, The Holy Father, Theology on 11.12.2009

It's been a while since I've said much about the whole reason I started this blog in the first place. After all, what would In Umbris Sancti Petri be without the successor Petri?

So what is the pope up to these days, you might ask?

Well, aside from promulgating apostolic constitutions that bring Anglicans back into communion with Rome and making pastoral visits to his flock (at home and abroad), Pope Benedict has been doing what good popes do. That is, teaching the faith.

Most recent on the roster of papally endorsed lessons has been the historical development of monastic and scholastic schools of theology--a trend that endures also throughout Ratzinger's earlier work. Since its October 28th inception at the Wednesday audiences, the topic has seen two subsequent installments; which leads one immediately to the question: "Why?"

Naturally, as an interested student of philosophy and theology myself, I'm a big advocate of the integration of faith and reason. And I think that Pope Benedict's persistent teaching on the importance of understanding Catholic intellectual history is evidence that, even at the level of the Church universal, the integration of faith and philosophy is absolutely critical for our very salvation.

In a recent post about Edith Stein, I stressed the importance of a Christian philosophy; and I cited St Thomas Aquinas as a key example of such a synthesis. But here I want to touch rather on the idea that each individual Christian--insofar as he or she is a Christian--must also necessarily be a Christian philosopher.

If a "philosopher" is one-who-loves-wisdom, then it should come as no surprise that for the Church to endorse philosophy is nothing else than for the Church to endorse a love of Christ, who is the spoken Word of God himself. In his book, The Nature and Mission of Theology, Ratzinger writes that:

If a "philosopher" is one-who-loves-wisdom, then it should come as no surprise that for the Church to endorse philosophy is nothing else than for the Church to endorse a love of Christ, who is the spoken Word of God himself. In his book, The Nature and Mission of Theology, Ratzinger writes that:

As early as the second century, Justin Martyr had characterized Christianity as the true philosophy, for which he adduced two main reasons. First, the philosopher's essential task is to search for God. Second, the attitude of the true philosopher is to live according to the Logos and in its company; that is why Christians are the true philosophers and why Christianity is the true philosophy.Furthermore, Ratzinger also claims that there is something else distinct about the Christian philosopher. While he uses his intellect to discern the truth of reality through natural reason, he also "carries in his hand the Gospel, from which he learns, not words, but facts. He is the true philosopher, because he has knowledge of the mystery of death." This problem of death, he says, is the "only real existential question facing man" after all; and it is because of the inescapable reality of death (and of its significance and role) that the Christian can ultimately make any sense of Christ'a Passion and Resurrection--the very core of the Christian faith.

Insofar as each of us faces this harsh reality, then--and insofar as we face anything which is simply beyond us--we are true philosophers. Moreover, inasmuch as we resolve the tension of these conflicts by an assent to faith in Christ (who conquers and makes sense of what is innately senseless) we are each Christians. And insofar as the two coincide--which they must quite necessarily--we are indeed Christian philosophers. Quite simply, we make sense of the mysteries we encounter not merely by natural knowledge, nor by supernatural faith, but by an integration of both.

And this is precisely what we are designed to do.

'Respectful' Research: A Gross Misrepresentation

Posted by Andrew Haines in Church Doctrine, News, Philosophy on 11.05.2009

Well, I suppose I should have seen this one coming.

Recently, the pharmaceutical group, Neocutis--which specializes in the production of burn treatments and skin creams--cited a 2005 Vatican document from the Pontifical Academy for Life in defense of its implementation of aborted fetal tissue research in the manufacturing of biomedical products.

Edith Stein: A New Look at Catholic Philosophy

Posted by Andrew Haines in Philosophy, Saints, Theology on 10.30.2009

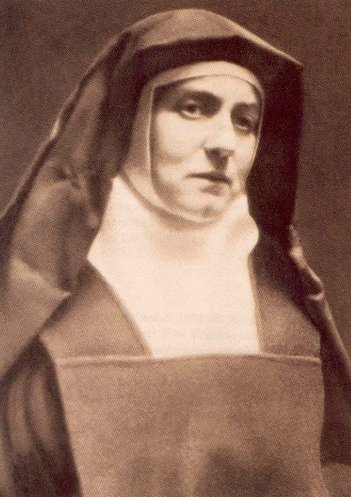

Each spring semester, the M.A. Philosophy Department at the Franciscan University of Steubenville holds a conference on some particular topic of study in the field of philosophy. Last year, the area of interest was Neoplatonism (in its ancient, mediaeval and modern contexts). And this year, in 2010, the conference will be devoted to the philosophical works of Edith Stein--also known as St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

Each spring semester, the M.A. Philosophy Department at the Franciscan University of Steubenville holds a conference on some particular topic of study in the field of philosophy. Last year, the area of interest was Neoplatonism (in its ancient, mediaeval and modern contexts). And this year, in 2010, the conference will be devoted to the philosophical works of Edith Stein--also known as St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

Nevertheless, though, her philosophical rigor was tempered very much by an appreciation of revealed truths as equally-given in the first moments of one's experience of reality. In other words, Stein--very much like Aquinas, in his own sort of Neoplatonism--considers the Trinity as co-given alongside the impressions of "being" that arise from an Aristotelian investigation of the world. For both Stein and Thomas, the Logos (reason, understanding) is not something deduced from real-world experiences; but rather, it is something within the context of which all real-world experiences abide. As such, God-as-Logos (i.e. the Word, or the Second Person) is a co-given reality, without which an authentic understanding of the world (and of metaphysics) is simply not possible.

Nevertheless, though, her philosophical rigor was tempered very much by an appreciation of revealed truths as equally-given in the first moments of one's experience of reality. In other words, Stein--very much like Aquinas, in his own sort of Neoplatonism--considers the Trinity as co-given alongside the impressions of "being" that arise from an Aristotelian investigation of the world. For both Stein and Thomas, the Logos (reason, understanding) is not something deduced from real-world experiences; but rather, it is something within the context of which all real-world experiences abide. As such, God-as-Logos (i.e. the Word, or the Second Person) is a co-given reality, without which an authentic understanding of the world (and of metaphysics) is simply not possible.'Faithful' Dissent: Where's the Line?

Posted by Andrew Haines in Church Doctrine, Liturgy on 10.26.2009

During my days as an undergraduate student at a (Jesuit) Catholic university, one could pretty well count on the fact that most campus ministers would define themselves, proudly and primarily, as 'faithful dissenters.' "I am Catholic," they would invariably admit, "but the Church is really behind the times on [insert dogmatically defined issue here]." From small-group leaders to musicians to sacristans, almost anyone involved in serving the Catholic community at my college was somehow at odds with some aspect of Church teaching.

And in all cases--on the heels of such discordant convictions--their 'ministry' to the community suffered. Instead of attesting to the truth of the Church's magisterial authority with their very lives, they spent most of the time discussing why such-and-such was holding them back from really living out an authentic Christian vocation.

Five years after those tumultuous (and tiring) days as an undergrad, I still can't seem to escape the phenomenon of 'faithful dissent.' And, what's more, of 'faithful dissent' coupled closely with a desire to minister to the people of God. In particular, an encounter I had just last month reawakened many questions that had, for a while, lain dormant in the back of my mind. Now, again, they persist.

For the last few months, I've been heading up the Gregorian chant schola at my local parish. After singing at a Mass the other weekend, the parish organist/music director approached me to discuss how Mass had gone. "You sounded good," she said, and proceeded to mention her thoughts on chant, music and our schola as a whole. "Gregorian chant is nice," she finally said, with a bit of a chagrinned look on her face, "but I don't want to go back."

"Go back to what?" I asked.

"Back! This diocese has a tendency to go back, not forward," she suddenly retorted. "And I don't know why! It's not doing what all the other dioceses are doing; and I think our diocese needs to realize that the past is not the answer. The Church needs to realize that it won't go anywhere until it reconsiders how it does things--and starts to let women up there!" She pointed toward the sanctuary.

In less than a minute, our friendly discussion of liturgy and music degraded into a diatribe against the male, celibate priesthood, and the very foundations of the Church's teaching authority. Without so much as hinting at a reason, our music director had bypassed all logical segues and proceeded directly into a rant about 'antiquated' rituals and mediaeval hierarchical nonsenses. However, I have to admit that (sadly) I was not all that surprised. And I immediately thought back to those folks at college--those 'ministers'--whose energy was spent more on rationalizing and justifying than on serving and teaching.

In light of this most recent run-in, I'm left with the same perennial questions: namely, is it really possible for someone who dissents from a dogmatic teaching of the Church--and who dissents so vehemently--to be an authentic minister of that Church? Or, to put it a different way, what's the line beyond which one's actions in the name of the Catholic Church cease to be effectively Catholic, and start to be effectively something-else?

For my old college campus ministers, being a 'faithful dissenter' was a badge of pride; and they wore is courageously on their breasts (probably alongside a rainbow ribbon and a "Catholics for Choice" button). For my present colleague, 'faithful dissent' seems rather to arise from some long-held resentment, which betrays a deep and fundamental divergence from the faith of the Catholic Church. In both cases, Christians feel a desire to serve others; but it is a desire weighted down heavily by the burdens of constant complaint, disagreement and capriciousness. In either case, the very bedrock of ministering to others "in the Catholic tradition" (as some are wont to phrase it) is utterly compromised by the desire to hold in tension two conflicting and diametrically opposed viewpoints--i.e. that of the Church, and that of unwavering personal opinion.

Certainly, there is no easy answer to this dilemma. It is an ubiquitous one both in America and throughout the entire world. But it raises deep questions that ought to be dealt with, lest we lose sight of the responsibility of Christian ministers--in whatever capacity--to serve with honesty and integrity. If one can only give to others so much as he or she has received from the first Giver, then how much of a unified, true message can one convey who himself sees truth as negotiable and unity as simply an option?

To minister to others requires that we first be ministered to by the Church herself. If our understanding of that Church promotes any sort of disunity among its members, then we are not aspiring to the true Christian Church. And if we are not ministers of the true Church, we are not ministers to the faithful of that Church after all.

Pro-Life Updates

Posted by Andrew Haines in News on 9.20.2009

Much has happened since our last encounter! And although I can't possible share it all here, suffice it to say that changes in my own employment status (from "non" to "employed") have really taken away a vast chunk of my free time. So, once more, I was forced to stop writing for a while.

As many of you know, another project that's eaten up quite a bit of time—and that is currently picking up steam once again—is the movement I've helped to found: ProLife | ProPatria. In the last few weeks, lots of new things have happened—including the advent of a few new writers/editors, some leads on important connections, and the creation of a new website that will be launched by the beginning of October (same URL: www.prolifepropatria.com).

As always, I'll try my best to make some time for this site; but most of my 'teaching' efforts will have to be put forth both at school, and with the movement. If you've been a follower of this blog for long, ProLife | ProPatria will be a nice addition to your RSS feeds; and the content we discuss—coupled with the new array of fresh writers—will certainly pique your interest!

So stay tuned, and venture over to check it out!

Duruflé's Messe "Cum jubilo"

One of the most interesting things I've been a part of in recent months (or really ever, for that matter) has finally come to fruition. No, not my M.A. But it's almost as good!Last Spring, the choir of the Pontifical North American College recorded a full-length CD of a Mass setting by the 20th century French composer, Maurice Duruflé. The record, his Messe "Cum jubilo" is now available through JAV Recordings here. For anyone interested in classical/sacred music, it's a great buy!

Altogether, the CD is an entire Mass (sung the way it ought to be!) comprised of both Gregorian chant (Introit, Alleluia, etc.) and Duruflé's compositions of the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus/Benedictus and Agnus Dei. It even includes all the prayers, propers and readings from the Mass of the Immaculate Conception—the College's patronal feast.

What's more, there's a great deal of organ improvisation as well, done by one of the most influential and noted organists in the world today: Stephen Tharp. From the bells on the first track to the organ sortie on the final, this recording is something worth checking out. Even the CD booklet has some cool pictures, and some interesting (and meditative) shots of the NAC that some might enjoy. (The cover photo, above, is the mosaic in the apse of the Immaculate Conception chapel at NAC.) Plus, you'll get to hear me sing—and you'll be supporting a good cause.

So visit JAV and pick up a copy. And play it for your kids. They will like it too! [And if they don't, you can teach them!]

Three "I-Know-Not-Whats"

Posted by Andrew Haines in Church Doctrine, Church Fathers, Theology on 6.09.2009

In honor of the Feast of the Holy Trinity, a fellow blogger at I Limoni posted a quote from Msgr. Luigi Giussani that reads: "La Trinità vuol dire che la natura dell'Essere è comunità" ('The idea of the Trinity is to say that the very nature of being is "community"').

How often we forget about this element of our Catholic faith: the Holy Trinity. Rarely do we hear prayers addressed to the Trinity as such; rather, we generally approach the Father, or the Son or the Holy Spirit by themselves. In fact, our faith teaches this as well, that certain qualities or characteristics are associated with certain persons. But how often do we stop to think, "What does it mean to say God is three persons in one God?"

![]() Without launching into an extravagant historical analysis of all this, it suffices to say that understanding God to be three persons in one substance goes all the way back to the early Church writers—and particularly the Cappadocian Fathers, like St. Basil the Great. For almost two-thousand years, the Church has interpreted Christ's revelation of the Father and Spirit in terms of person, or 'one in relation to another.' This is evidenced in writers like Tertullian, Athanasius, and in Basil's work especially; and it is a teaching that has endured throughout the centuries.

Without launching into an extravagant historical analysis of all this, it suffices to say that understanding God to be three persons in one substance goes all the way back to the early Church writers—and particularly the Cappadocian Fathers, like St. Basil the Great. For almost two-thousand years, the Church has interpreted Christ's revelation of the Father and Spirit in terms of person, or 'one in relation to another.' This is evidenced in writers like Tertullian, Athanasius, and in Basil's work especially; and it is a teaching that has endured throughout the centuries.

On the other hand, despite being able to say that there must be some relation/community in God, the idea of how that ought to be formulated has had a much rockier road. There are a myriad of various (and accurate) descriptions of the Trinitarian life, also tracing back to the early fathers, and culminating (more or less) with the Cappadocian formulation. But that doesn't mean it hasn't undergone serious challenge and 'constructive criticism' since then.

One of the best examples is that of St. Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033AD), who even called God "three substances in one person," rather than the traditional "three persons in one substance." Although Anselm reversed the formulation, he probably did it with a specific goal in mind: to show that the Trinity is a dynamic being; and that each Person (while not a 'substance' in the classic sense) is nevertheless a subsistent relation. But this varied formulation seems to lack a certain clarity (and doctrinal force) that is maintained in the traditional formulation. In fact, Anselm concedes in the end that God is a Trinity "because of the three I know not what" (propter tres nescio quid).

One of the best examples is that of St. Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033AD), who even called God "three substances in one person," rather than the traditional "three persons in one substance." Although Anselm reversed the formulation, he probably did it with a specific goal in mind: to show that the Trinity is a dynamic being; and that each Person (while not a 'substance' in the classic sense) is nevertheless a subsistent relation. But this varied formulation seems to lack a certain clarity (and doctrinal force) that is maintained in the traditional formulation. In fact, Anselm concedes in the end that God is a Trinity "because of the three I know not what" (propter tres nescio quid).

The underlying point, though, is that God is Trinity; and that the Trinity is a personal community. The Father is the Father only because he stands in relation to the Son. And the Son is the Son only because he stands in relation to the Father. These relations are subsistent relations, in that they account for the very identity of the ones in relation (i.e. the divine persons).

Really, struggling with the idea of the Holy Trinity is something eminently Catholic; and something that the greatest minds and saints have been doing now for two millennia. We should continue to do the same thing, and continue to address God under his majestic and solemn title: Sancta Trinitas, unus Deus.

What's the Deal with Liturgy?

"Everything's better in Latin," say the 'traditionalists.' "Why do anything other than the red and say anything other than the black?"

On the other side of the fence, the über-progressivists contend that Mass ought to be anything but cookie-cutter. "Jesus is present in the people, and people are dynamic and alive, so Mass should be too."

Finally, for the pietists, "Mass is Mass; and as long as Jesus is present, that's all that matters."

[N.B. For those who don't care for sweeping generalizations, this post is not for you.]

So, again we ask: "What's the deal with liturgy, anyway?" Why all this hubbub about the Mass? In a few short lines, we are able to class the vast majority of liturgical sensibilities into three (fairly) tight-knit groups; and despite the (resounding) accusations that such categories are naïvely cliché, the fact is that stereotypes arise from empirical data. After all, there's probably a reason that we don't speak about neo-Arians and hyper-Origenists: no one cares. But something about the liturgy fascinates people; and it fascinates them enough to divide them into distinct and undeniable camps (regardless of what we decide to call them).

Whatever's at the heart of all this debate about the way the Mass 'ought to be' is certainly a powerful concept. It's something that must strike to the core of what it means to be a Catholic, or at least a Catholic in the twenty-first century. No doubt, this central issue is deeply connected to various ideas of how the Church ought to interact and exist in the modern world. The question of liturgy is one that permeates the entire Christian life, since it is a question of man's openness to the divine, and his practice of worshiping God, the Creator of all that is.

Really, it's this last notion, I think, that forms the real edge of liturgical disagreement and dialogue. The idea that the Catholic liturgy is the prima theologia is undeniable, even for those who are far from being theologians in any other respect. There is something unavoidably 'theological' about Mass; and I think this inevitable sense of encounter is what makes liturgy such a touchy topic.

In fact, I would be remiss in failing to admit that a certain facet of this concept of prima theologia is present in all three of the liturgical camps I mentioned initially. For the 'traditionalists,' it is apparent that the Church's authority to discern the appropriateness and fittingness of certain liturgical activities is absolute. The Church is the Body of Christ, and she is reliant upon her divine Head (whose Vicar is the pope) to distinguish what will benefit the entire Body as a whole. For the 'progressivists,' the idea of dynamism is ever present; and a dynamism that really does capture the reality of a Body fully alive. The same Body of Christ is ever growing and developing in its environment. It is the Body of a divine Person, but in human form. And for the 'pietists,' there is the simple fact that "God alone is enough." No matter the form of the Mass, or the political agendas vying for supremacy, the really important thing is that God-made-man is present among us; and we, as a Church, are there to pay him homage.

In some way, perhaps, this distinct, tripartite theologia is actually a Trinitarian theology. In other words, each emphasizes a Person of the Trinity which, unless seen in relation to the others, loses its relational subsistence. God the Father is the ungenerated font of all being, and of all Truth. He is the source of all reality, and the ultimate term by which are understood the Son and the Spirit. Accordingly, the Holy Spirit is the dynamic breath of the Father, sweeping through his creation and imbuing it with life. And finally, the Son, Jesus Christ, is the vision of the Father. He is the way we approach the Father, and the one to whom all praise and honor is due.

Ultimately, the trick with any 'theology' is in coming to get all the parts to fit together. And this is without a doubt the trick with liturgy. But the more we come to appreciate the individual contributions of any given liturgical sensibility, the more we'll come to see the Mass as a real prima theologia; and as the true vision of the Paschal Mystery that it is.